Rating for Wildfire Risk

The Canadian insurance industry’s recent experience with wildfire has been expensive and if climate scientists are correct, the problem is going to get worse in coming years. Canada has a tremendous amount of vegetation and forested land from coast to coast, and Canadians love to build communities that highlight the beauty of forests and trees. In many communities, the desirability of the subdivisions is increased by building dwellings right into the forest and by limiting the disruption of the forest as much as possible. Trees and forests provide a beautiful backdrop for homes and provide privacy and shade when they are in close proximity to dwellings and residential subdivisions.

The wildfire problem

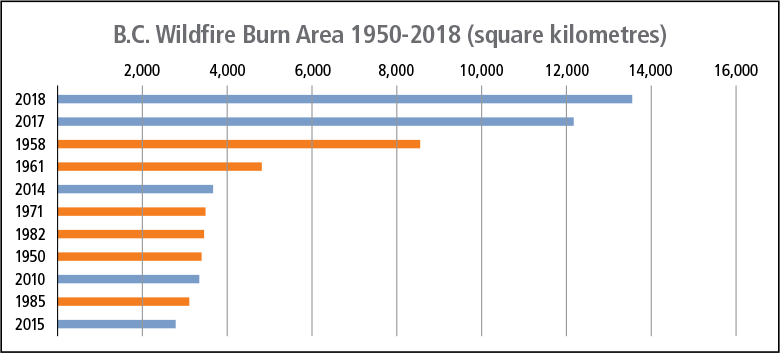

The records just keep piling up. At the peak of the 2018 wildfires, more than 40,000 people in dozens of communities were forced to leave their homes. Another 20,000 people were on evacuation alert. Early estimates have 2018 as the largest total burn-area in any British Columbia wildfire season with an estimated 1.3 million hectares burned.

This kind of record-breaking fire season would normally be an anomaly that stands out from other data points, but in this case, it is looking more like a trend. The 2017 year was also a historic wildfire season with more than 65,000 B.C. residents evacuated and more than 1.2 million hectares burned.

We weren’t alone in this. During the autumn months of 2018, U.S. news outlets broadcast heartbreaking footage of wildfires in California. The Insurance Information Institute (www.iii.org) reports that close to 30,000 structures were destroyed. While there were fewer fires in California in 2018 compared to the previous year, they were far more destructive in terms of loss of life: at least 88 people perished in 2018 compared to 23 in 2017. The California Dept. of Insurance reported that at almost $12 billion, the 2017 fire season was the costliest on record. However, the 2018 Camp and Woolsey fires are likely to exceed that cost when insurance losses are added up.

The images from California were a painful reminder of 2016, when the most severe insurable catastrophe in Canada’s history occurred in Fort McMurray. People around the world watched in shock as video footage of people driving through a raging inferno was shown on every newsfeed day and night. Amazingly, 90,000 people were evacuated successfully in a very short period of time with only one tragic fatality in a motor-vehicle accident during the mass exodus. The event destroyed approximately 2,400 structures and the cost of insured damages reached approximately $3.6 billion.

And there have been other severe events in the past 20 years in western Canada. In 2003, the Okanagan Mountain Park Fire in Kelowna destroyed more than 300 homes and businesses and forced the evacuation of more than 45,000 people. The cost of insured damages reached approximately $200 million. In 2011, the Slave Lake Fire destroyed more than 400 buildings and damaged many more. The fire caused $750 million in damages.

Contributing factors

Wildfire events happen every year across Canada and in cases where they are not near human settlements, they typically do not attract a lot of attention from the Cana-dian public or the insurance community. However, when wildfires threaten human settlements and insurable property, they attract a lot of attention.

The National Forestry Database shows that typically more than 8,000 wildfires occur across Canada each year and burn an average of more than 2.1 million hectares. Over half of wildland fires are started by people, most by accident, and just under half by lightning; however, fires started by lightning account for roughly 10 times the burned area of humancaused fires. Most recorded wildland fires are very small and are less than .01 ha (100 square metres) in size. Two per cent of wildland fires account for 98% of total burned area each year.

Wildfires are natural disturbances that play a vital part in the cycle of renewal of boreal forests. Other natural disturbances including insects and disease outbreaks, drought, and floods have been happening in Canada’s forests for thousands of years. These natural events are part of the life cycle of the forest and generally help the forest to renew itself.

Canadian forests have evolved to grow thicker and thicker for decades, then burn off (or die off due to other causes) and then renew themselves with vibrant regrowth. Forest fires are the primary change agent in the boreal zone, and are as crucial to forest renewal as the sun and rain. Forest fires release valuable nutrients stored in the litter on the forest floor. They open the forest canopy to sunlight, which stimulates new growth. They allow some tree species, like lodgepole and jack pine, to reproduce, opening their cones and freeing their seeds.

Our current forest mansignificantly influencing this cycle. Historically wildfires would burn freely until they burned themselves out; however, currently, wildfires are almost always put out. This practice interferes with the natural renewal process and results in more dense vegetation to burn and more severe conditions of accumulation of combustible material.

Two other major factors are also causing increasing trends in the severity of wildfire risk and its impact on Canadians and the insurance industry. One is development and land use and the increasing tendency to build in, or near, forested lands. The number of buildings (particularly dwellings) being built in and around forests is steadily increasing as urban growth pushes into the surrounding wildlands. The other factor is climate change, which is having the effect of making the weather factors more intense. Areas that had hot and dry seasons are becoming hotter and drier, and this increases the risk of wildfire as fuels on the forest floor become drier and more likely to ignite.

In wildfire-management circles, there’s a 30-30-30 rule that is often referenced as the condition that signals imminent danger of wildfire ignition and spread. When temperatures rise above 30 degrees Celsius, relative humidity drops below 30 per cent, and wind speeds rise above 30 kilometres per hour, the risk of wildfire is high. All three of these factors are influenced and made more frequent and severe by climate change.

NASA’s Global Climate Change website (https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence) indicates that the average temperature has risen by 1.1°C since the late 19th century, with most warming occurring over the past 35 years; 16 of the 17 warmest years have occurred since 2001. High-temperature events have been increasing while low temperature events have been decreasing, and this ongoing trend is continually increasing the risk of severe wildfire events.

Dealing with wildfire

Jurisdictionally speaking, wildland fires are handled by the provinces. At the national level, the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC) has been formed to coordinate the sharing and use of resources between the provinces, territories, and the federal fire-management agencies, and when needed, the sharing of resources with the United States and other countries.

Municipalities, unincorporated communities, and First Nations communities typically are responsible for providing their own fire protection within their own boundaries; however, when wildfires encroach on the areas within communities, the provincial and local agencies must work together.

One of the significant findings of the Fort McMurray post-fire analysis conducted by KPMG was that inter-agency communications systems were not effective. For example, agencies’ emergency communications systems were not inter-operable, and agencies had to develop work-arounds on the fly during the response. After the Fort Mac fire, KPMG was contracted to conduct a post-incident analysis. By the time KPMG reported out, work was already underway on many of its recommendations, including one to develop an Emergency Management Communications Interoperability Plan that would facilitate communications flow between all stakeholders during emergency events. The lessons learned from Fort Mac and other large-scale disasters continue to inform the inter-agency strategies1 of the federal and provincial governments.

The largest issue for dealing with wildfire (if the intent is suppression) is capacity. As noted, community fire departments are not designed or resourced to deal with the scale of events that happen when wildfires affect human developments. Typical municipal fire departments have resources to deal with one structure fire at a time. Major wildfire events can involve more than 100 structure fires happening simultaneously. Local fire departments just don’t have the resources to deal with that scale of event.

Provincial resources for dealing with wildfires are at or nearing their capacity as well. Spending on suppressing wildfires in Canada is often in the billion-dollar-per-year range and provincial agencies are advising that they are using every resource they have at the peak of the wildfire season. With wildfires becoming larger in terms of size, frequency, and severity, the limits of provincial agency resources are concerning.

Keep in mind that due to the size and scale of the events, it is far more practical to invest in mitigation strategies than to invest in suppression capacity. Since the 1990s the non-profit group Partners in Protection has been developing the FireSmart2 program and promoting its use across Canada. This group has worked to bring together stakeholders to develop and make available resources for communities to mitigate the wildfire (urban interface) risk locally. Unfortunately, the program has had limited uptake at the community level to date. There are currently fewer than 100 recognized FireSmart communities listed on its website, which represents less than one per cent of incorporated and unincorporated communities across Canada.

Typical municipal fire departments have resources to deal with one structure fire at a time. Major wildfire events can involve more than 100 structure fires happening simultaneously.

Building in wildfire resilience

The Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction and Insurance Bureau of Canada are working with the National Research Council to have the National Building Code (NBC) changed to improve building resilience to wildfires.

The NBC typically defines a minimum requirement that can be applied nationally. Provinces adopt the NBC and increase those minimum standards where needed. For example, the B.C. Building Code3 increases the NBC’s minimum standards for moisture barriers in the coastal climatic zone, and seismic standards in earthquake-susceptible areas. The building codes may be adjusted again by municipal bylaws and are enforced at the municipal level.

Improving the building code, while extremely important, can take several iterations (five years each) to get to a point that is reasonably effective, and the building code is mainly applied to new construction, less so to existing building stock. Considering that new buildings make up a very small percentage of each insurers’ portfolio, the changes to codes will help in the long term, but are not likely to have a significant impact in the near term.

An increasing number of states in the U.S. are adopting the International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (WUIC) to assist with managing wildfire risk to their communities; however, currently no Canadian provinces have adopted this code.

The standards within a WUIC will vary according to regional needs, but typically include:

- Structure density and location: number of structures allowed in areas at risk from wildfire, plus setbacks.

- Building materials and construction: roof assembly and covering, eaves, vents, gutters, exterior walls, windows, non-combustible building materials.

- Vegetation management: tree-thinning, spacing, and trimming; removal of vegetation under tree canopies, and landscaping.

- Emergency vehicle access: driveways, turnarounds, emergency access roads, marking of roads, and property address markers.

- Water supply: approved water sources and adequate water supply.

- Fire protection: automatic sprinkler systems, propane tank storage.

The National Research Council Canada is currently developing new guidelines to address overheating in buildings, flooding resilience, and wildfire-urban interface design. The WUIC requirements of the NBC are reported to be an opt-in component and not part of mandatory section of the code. In this way, provinces or municipalities will be able to opt into the regulation if they feel it applies to their area and if they want to improve their management of the risk.

A new index

Insurance companies need better information about the risk of wildfire across their portfolios so that they can manage their exposure, and encourage the changes that help to mitigate the risk. Similar to giving credits for backflow preventers being installed in areas where sewer backup is known to be a risk, insurers can encourage mitigation of wildfire risk in areas that are known to have wildfire risk.

Insurers need a system that is standardized across their Canadian portfolio so that the results are consistent and can be easily integrated into their digital underwriting systems. For this reason, the Canadian Wildfire Grading Index4 has been created to provide insurers with standardized measures of wildfire risk across Canada.

The Wildfire Grading Index benchmarks the relative level of wildfire risk for all locations across Canada. Importantly, the system allows insurers to measure the wildfire risk across their portfolio in a standardized way for all properties they insure across Canada. The index considers the variables that have been identified as being the most significant and influential in terms of wildfire risk, such as climate factors, vegetation, soil, topography, and proximity to suppression resources.

This system will help insurers understand and manage the wildfire risk and provide a feedback loop that helps property owners, community stakeholders, and regional and provincial agencies to engage and participate in the measurement and mitigation of the wildfire risk.

The system incorporates many data sources from federal, provincial, and local governments and is designed to continuously improve as better data becomes available.

One of the most important features of the system, which follows the same concept as the Canadian Fire Insurance Grading Index, is that the indexed risk is adjusted based on best practices of suppression and mitigation. In the case of wildfire risk there is widespread agreement that the best practices for mitigation include implementation of FireSmart at the property, subdivision, and regional levels. As such, these factors have been included in the Index. Communities can report on implementation of FireSmart and receive credit that adjusts the measured wildfire-risk levels.

Once property insurers are able to take into account the level of wildfire risk, property owners, communities, and regional agencies will have an increased incentive to engage in the process of measuring and mitigating the risks.

Wildfire is a significant concern for the Canadian P&C industry, but with the integration of the best information possible, insurers can manage the risk and even help their clients to be as prepared as possible. Brokers are encouraged to talk to their underwriters about the implementation of the Wildfire Grading Index on insured properties within wildfire-interface areas.

Licensees can earn a CE technical credit. Go to https://ibabchyperarticles.com

Originally published in BC Broker